Past Winners of the Gene E. & Adele R. Malott Prize for Recording Community Activism

Past Winners of the David J. Langum Sr. Prizes

2023 | 2022 | 2021 | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007

2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001

For the year 2023

The Winner of the 2023 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is Before the Movement: The Hidden History of Black Civil Rights, by Dylan C. Penningroth

In this capaciously conceived study, Dylan Penningroth looks beyond the familiar narrative of the post-Civil Rights Movement to explain how Blacks used the law in their daily lives to promote their rights, going back as far as the era of slavery. His meticulous research, which draws upon the archives of his own family, demonstrates how Blacks effectively made use of the the law of contracts, property, tort, domestic relations, and inheritance. By providing a more expansive and nuanced understanding of Black freedom, Before the Movement is a transformative achievement. – D.S.

For the year 2022

The winner of the 2022 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction is Mercury Pictures Presents, by Anthony Marra

Anthony Marra’s gripping Mercury Pictures Presents explores an unusual and carefully researched perspective into World War 2. Split between Hollywood and an Italian prison camp, the novel follows several interconnected lives at the point when America is just about to enter the war and shortly after. At the centre is Maria Lagana, an Italian political prisoner’s daughter and ambitious associate producer for a B-movie studio, “a job that demanded the talents of a general, diplomat, hostage negotiator, and hair-dresser”. The novel plays with viewpoint, surveillance and artifice. In a sudden reversal, Mercury Pictures shifts from defending itself in Congressional hearings about promoting pro-war messages to producing propaganda films for the War Department. Ultimately, they combine enemy propaganda and scenes produced in the studio rather than actual footage as “soundstage skirmishes look more realistic than the real ones”. While covering a full cast and wide geographic scope, Marra creates richly realized characters in vivid prose. Throughout, the story is comic, absurd and touching. – V.L.

– – – – –

The finalist of the 2022 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction is The Magic Kingdom, by Russell Banks

The protagonist, Harley Mann, then an eccentric and somewhat crotchety old man, dictated these fictional memoirs into a tape recorder on the porch of his modest home in St. Cloud, Florida. Mann’s early years were spent with his family in an Indiana Ruskinite commune. The father’s ideological differences caused the family to move. This rigid adherence to principle ultimately hurt his son, Harley, as well. They settled in Florida in miserable conditions. The father then died, and Mann’s mother made a connection with a Shaker colony, New Bethany, located in the general vicinity of the present-day Disney World.

They arrived in New Bethany in 1902, and Mann grew into early adulthood there as a trusted young man who could not formally become a Shaker until he was 21. At age 12 he met Sadie Pratt, a sufferer from consumption and who lived at a hospital colony near New Bethany. When the hospital collapsed financially, she moved to New Bethany. Mann gradually fell into an obsessive love for Sadie, and after she moved to New Bethany they became lovers. We know that Pratt was attractive and about six years older than Mann, but not much else. Although one might ordinarily think of her as an undeveloped character, we must bear in mind that the entire affair is told, long after the fact, by an old man recalling an obsessive love. Pratt’s condition turns to the worse, and she dies, in a tangle of circumstances that result in Pratt’s accusation to the authorities that the leading elders over-administered her morphine. In turn, this leads the Shaker community to shun their accuser.

It is unusual that an historical novel dwells on the Shakers, but here they are given full attention, showing their beliefs, rituals, and practices. Another feature of the book, also fresh, is its consideration of riverboats as the usual method of transportation in middle Florida in the early 20th century. The book is engaging, and the narrative voice holds the reader well. – D.J.L. Sr.

– – – – –

The Winner of the 2022 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is The Sewing Girl’s Tale: A Story of Crime and Consequences in Revolutionary America by John Wood Sweet

In this riveting and exhaustively researched account of one of the first rape trials, The Sewing Girl’s Tale brilliantly surveys the intersection of gender and class biases in its vivid portrayal of the social, cultural, and economic life of 1790s Manhattan and exposes the tensions between the democratic ideals of the new republic and the persistence of oppression of women and the working classes. In recreating the long-ago world of Lanah Sawyer, the aggrieved seamstress, John Wood Sweet provides an inspiring example of how disadvantaged persons can challenge injustices and shape their destinies in the face of great obstacles. – W.G.R.

– – – – –

The Finalist of the 2022 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is Democratic Justice: Felix Frankfurter, the Supreme Court, and the Making of the Liberal Establishment by Brad Snyder

In his exhaustively researched, deftly written, and timely biography of Felix Frankfurter, Brad Snyder helps us make sense of an often misunderstood and mischaracterized member of the modern Supreme Court. At a moment when the Court holds far less promise as an engine of social reform, Democratic Justice: Felix Frankfurter, the Supreme Court, and the Making of the Liberal Establishment paints a picture of a jurist whose ideology we are only now more fully equipped to appreciate. – D.S.

For the year 2021

The winner of the 2021 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction is Ridgeline, by Michael Punke

This is the story of a battle that delivered the U.S. Army its second largest loss of the Indians Wars, exceeded only by Custer’s debacle at the Little Big Horn. American accounts commonly refer to this as the Fetterman Fight or Fetterman massacre, occurring near Fort Phil Kearny in Wyoming. The local Indian tribes in a rare example of co-operation assembled over 1,000 warriors, and then used a strategy of decoy to lure about 80-100 American soldiers into a tight canyon around which the Indian warriors were hidden. Using a clever system of signals, the Indians were able to charge the Americans at a single instant and annihilate them.

It is more than just a war story in that the author carefully covers the Indian motivations. Well-told through fiction, entire chapters cover their historical grievances that led to this particular encounter and their careful planning. It is well-written and loaded with history, from both the American and the Indian perspectives. The book is an even-handed work of excellent fiction, loaded with history brought out in the narrative without being in the least bit pedantic or tendentious. A skillful job. – D.J.L., Sr.

– – – – –

The finalist of the 2021 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction is When the Stars Rain Down, by Angela Jackson-Brown

When the Stars Rain Down is a coming-of age story set in small-town Georgia in the 1930s. The summer heat is oppressive, as is the sense of foreboding for teenager Opal. Opal lives in “Colored Town,” an enclave of African-American residents of the fictional town Parsons. With her grandmother, Opal works as a housekeeper for a family she has known for her entire life and considers family. However, the strength of this bond is tested during several horrific incidents of racial violence in the town. These events force Opal to examine her relationship with her employers and community. In a simple and absorbing style, the novel draws the reader into Opal’s rich and complex inner life as she negotiates romance, religion and emotional labor and pain. With its tightly drawn historical context and characters, When the Stars Rain Down is a timely book. – V.L.

– – – – –

The Winner of the 2021 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is Traveling Black: A Story of Race and Resistance by Mia Bay

“American identity has long been defined by mobility and the freedom of the open road, but African Americans have never fully shared in that freedom,” Mia Bay writes in her extraordinary, elegant, and moving new book. From stagecoaches and steamships to trains, planes, and automobiles, travel throughout the nation has been the site of racial discrimination and African American resistance. Bay brilliantly demonstrates how travel became the flash point for racial conflict and reminds us how many Rosa Parks preceded Rosa Parks. This superbly researched story takes us beyond the courtroom to the actors who agitated to end segregation in transportation and demonstrates the changing–and continuing–ways they navigated race and shared space. Brava! – L.K.

– – – – –

The Finalist of the 2021 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is Vice Patrol: Cops, Courts, and the Struggle over Urban Gay Life before Stonewall by Anna Lvovsky

In this wide-ranging and imaginative study, Anna Lvovsky centers the law’s confrontation with gay life in the United States in the mid-20th century, training her eye on criminal justice at the local level. Lvovksy illuminates the tensions between, on the one hand, state liquor agencies established post-Prohibition and the newly-formed vice patrols of local police forces, and, on the other hand, state trial courts, where judges exercised discretion to temper what they viewed as bureaucratic and law enforcement excesses. While this story alone would render Vice Patrol an important addition to our burgeoning history of the American criminal justice system, the study is all the more important for a larger dynamic Lvovsky’s study reveals: that the project of policing gay life prior to Stonewall was not simply a contest over sexual practices or public conduct, but also was the site of an institutional struggle over the boundaries of the criminal justice system itself. – D.S.

For the year 2020

The Winner of the 2020 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction Is The Cold Millions by Jess Walter

Jess Walter’s The Cold Millions is a novel of the burgeoning Pacific Northwest that presents history through an engaging storytelling voice brimming with both humor and pathos. In the early 20th Century, Ryan “Rye” Dolan, a 16-year-old orphan, sets off from Montana in search of his older brother, Gregory (Gig). Finally reuniting in Washington state, Rye and Gig ride the rails, attempting to make ends meet amidst obstacles that include ruthless employers, corrupt job agencies, and Gig’s less than responsible approach to life. This approach leads Gig to join a group of idealists and later the Industrial Workers of the World. Rye is less than taken with the unions, which he sees as a sure-fire ticket to jail and beatings from local law enforcement. Despite his misgivings, Rye is pulled into the middle of the workers’ rights struggle when a beautiful young activist (the historical Elizabeth Gurley Flynn), travels to Spokane to stir things up. In a desperate attempt to free Gig from imprisonment for his union activities, Rye is forced into a devil’s bargain with a dangerous mining magnate. The history of this period of labor unrest is woven seamlessly into the plotting, allowing The Cold Millions to illuminate an era that is often overlooked. Walter’s characterization and multiple narrative perspectives, from Pinkertons to burlesques, add even more color to an already vibrant portrayal of the tramp lifestyle amid the industrialization of the Pacific Northwest. The result is an entertaining and riveting read. – B.L.

– – – – –

Finalist for the 2020 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction Is The Book of Lost Light by Ron Nyren (Black Lawrence Press, 2020)

Set in San Francisco and surrounding areas at the turn of the 19th century, this novel portrays the activities of an eccentric tiny family. The father, Arthur, is a portrait photographer, mechanical genius, and a somewhat unstable man. His wife died in the childbirth of their son Joseph, and the family is saved by the arrival of Arthur’s orphaned niece. She herself is a bit eccentric, but stable enough to keep Arthur in reality and to serve as a surrogate mother to Joseph. Arthur has some peculiar theories about the nature of time, and how he might capture the essence of time by taking a photograph of his unclothed son, Joseph, in the same pose at the exact same time of each and every day. The dynamics between father and son form the heart of this novel, and the reader can anticipate the time when Joseph as an adolescent ultimately rebels.

The prose is engaging and the descriptive passages illuminative. We read a vivid description of the San Francisco earthquake and its effects on the everyday citizenry of San Francisco. There is much here on the history of photography. Before Joseph was born, Arthur worked for Eadweard Muybridge, an actual historical person, at his experiments with the photography of motion that he conducted at Leland Stanford’s farm. There is considerable discussion of Muybridge and his and other early photographers’ work, and this gives the reader a good sense of the period and a feel for technological innovation in photography during this period. The book feels fresh. – D.J.L., Sr.

– – – – –

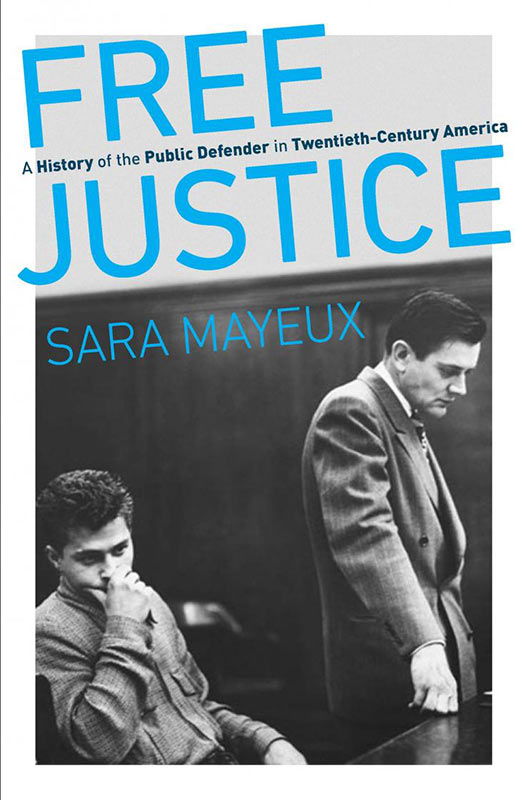

The Winner of the 2020 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is Sara Mayeux’s Free Justice: A History of the Public Defender in Twentieth-Century America (University of North Carolina Press, 2020). Mayeux is associate professor of law and associate professor of history at Vanderbilt.

This important, beautifully written book explores the emergence of the public defender during long Progressive era, a time when the United States faced the same paradox of poverty amid progress and wealth against commonwealth that it confronts today. The idea took wings even though white-shoe lawyers considered indigent criminal defense a job for private charity and equated public defense with socialism and totalitarianism. As was so often the case, the Cold War turned everything upside down. By the mid-twentieth century, elites had repurposed the public defender as a weapon of anticommunism, a way of showing American law’s special respect for individual rights—a way of vindicating the constitutional rights of defendants, especially the right to counsel that the Warren Court supposedly guaranteed in Gideon v. Wainwright. Mayeux powerfully challenges the standard interpretation that states were moving towards establishing public defender offices in the North and West and that Gideon accelerated that movement only in the South, where white supremacy reigned. She shows us how Gideon transformed the provision of legal services to criminal indigents across the United States—not always for the better. A big book that shows the legal profession and public defenders shaping and being shaped by society, Free Justice is neither a feel-good story nor another “lost promise of Gideon and the Warren Court” account. Mayeux brilliantly shows us roads not taken, highlights contingency, and shows us how matters might have turned out differently. And in reminding us of that, she enables us to imagine a more hopeful future. – L.K.

– – – – –

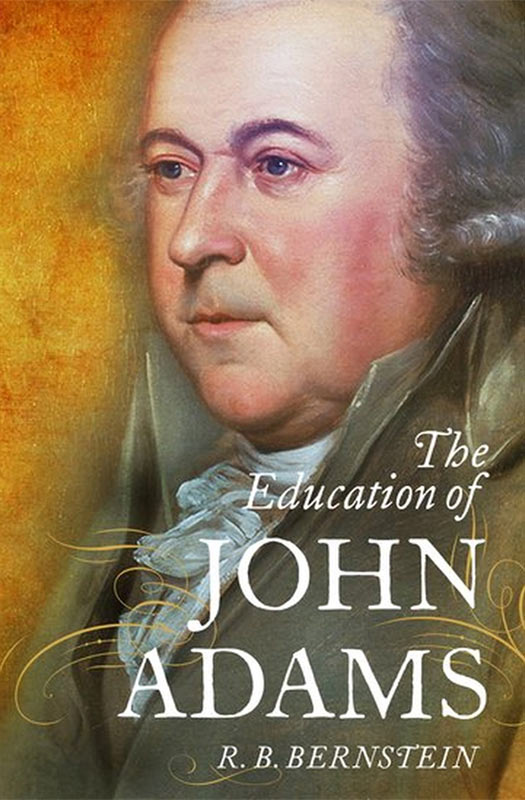

The Finalist of the 2020 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is Richard B. Bernstein’s The Education of John Adams (Oxford University Press, 2020). Bernstein is an adjunct professor at New York Law School.

For the year 2019

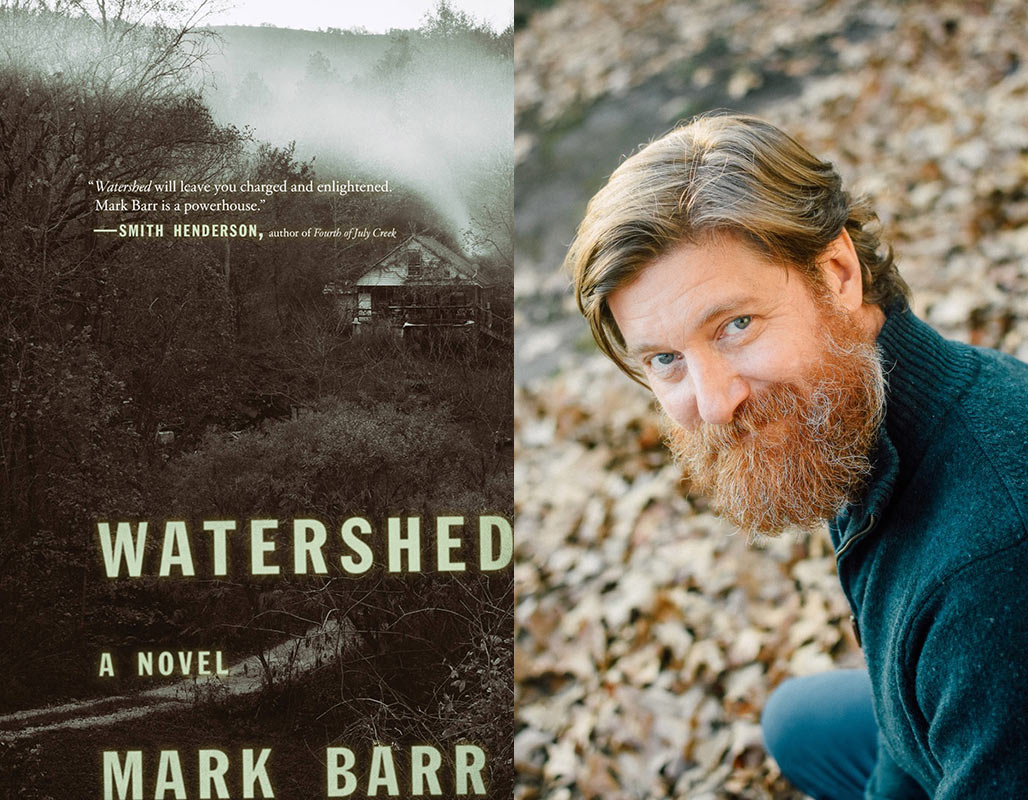

The Winner of the 2019 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction Is Mark Barr for Watershed (Hub City Press)

Reading Mark Barr’s Watershed is an immersive historical experience, a pitch-perfect evocation of a time, a place, and a culture. In the midst of the Depression, engineer Nathan McReaken attempts to evade a ruinous past. He arrives in a small Tennessee town to seek a new start building the federal dam nearby, an endeavor that will bring life-altering electrification to the homes of the valley’s rural inhabitants. There he meets Claire Dixon, a housewife attempting to forge a different path after estrangement from her husband. The dam provides new opportunities for Claire as well; she finds work convincing local households to sign on to an electricity co-operative. Nathan’s feelings for Claire deepen and Claire’s ambitions for her life shift, but forces beyond either’s control threaten all they have tentatively begun to build.

Reading Mark Barr’s Watershed is an immersive historical experience, a pitch-perfect evocation of a time, a place, and a culture. In the midst of the Depression, engineer Nathan McReaken attempts to evade a ruinous past. He arrives in a small Tennessee town to seek a new start building the federal dam nearby, an endeavor that will bring life-altering electrification to the homes of the valley’s rural inhabitants. There he meets Claire Dixon, a housewife attempting to forge a different path after estrangement from her husband. The dam provides new opportunities for Claire as well; she finds work convincing local households to sign on to an electricity co-operative. Nathan’s feelings for Claire deepen and Claire’s ambitions for her life shift, but forces beyond either’s control threaten all they have tentatively begun to build.

Barr effortlessly contrasts the cultural perspectives of urban-bred engineers and bureaucrats with that of the valley’s local population. The historical context paints a vivid picture of the advent of electricity, the anticipation of how its introduction would change fundamental daily rhythms from time out of mind. The sense of place, from the sticky Southern heat to the cornbread and butter beans, is wholly authentic. Conveyed in prose that simply but effectively illuminates, Watershed would be an accomplishment for any author, and is especially remarkable as a historical fiction debut. – B.L.

– – – – –

Finalist for the 2019 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction Is The Glovemaker, by Ann Weisgarber

Ann Weisgarber’s The Glovemaker is set in the late 1880s in the Utah territory. The novel captures both the beauty and peril of the natural environment in which the protagonist Deborah lives in a small community of Mormons. While Deborah and her neighbors live outside the official teachings of the Church and do not practice polygamy, fear and memory of Mormon persecution guides their practice of assisting Mormon fugitives. One of these fugitives threatens to break the community apart. With quiet and economical prose, the novel is clear and confident about the “in-between” world it depicts. – V.L.

Ann Weisgarber’s The Glovemaker is set in the late 1880s in the Utah territory. The novel captures both the beauty and peril of the natural environment in which the protagonist Deborah lives in a small community of Mormons. While Deborah and her neighbors live outside the official teachings of the Church and do not practice polygamy, fear and memory of Mormon persecution guides their practice of assisting Mormon fugitives. One of these fugitives threatens to break the community apart. With quiet and economical prose, the novel is clear and confident about the “in-between” world it depicts. – V.L.

– – – – –

Finalist for the 2019 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction is American Princess: A Novel of First Daughter Alice Roosevelt, by Stephanie Marie Thornton

This is a fictional biography of a fascinating woman, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of Teddy Roosevelt and doyenne of Washington’s social/political life for decades.

This is a fictional biography of a fascinating woman, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, daughter of Teddy Roosevelt and doyenne of Washington’s social/political life for decades.

I generally do not care for fictional biographies because, as an historian, I keep asking myself “how much of this stuff is real?” I never have that perplexing question for novels that I know are entirely made up. Here, however, in an author’s note at the end, Thornton goes to a considerable extent to explain what events she altered a bit, and a few things she made up entirely. And these are not that many.

It is a lively and fascinating read, written in Alice’s own voice, that describes a very raucous and forceful woman, uninhibited to the extent she had an illegitimate child with a married Senator, with whom she was having an affair whilst she herself was married to the Speaker of the House. Thornton is able to use the events of this affair and resulting love child, and other events as well, to build up more dramatic tension than is usual for a biography.

Because Alice Roosevelt Longworth was personally acquainted with many political and business leaders of the world, and because throughout the adult years of her 96 year life she was often involved in considering issues at very high levels, the book is loaded with history, mostly political history but also economic and social history. As the biography is organized chronologically, the history we are given is chronological rather than the analytical history – how things were socially and politically at any given time or place – most common to historical fiction. – D.J.L., Sr.

– – – – –

The Winner of the 2019 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is Sarah A. Seo for her Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom.

Sarah Seo’s Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom is an inventive interweaving of technology, society, and criminal procedure that reveals a paradox formerly unacknowledged but so obvious once pointed out: at the same time that the mass-produced automobile brought unprecedented mobility to a wide swath of American society, it also subjected people to an unimaginable level of government authority, utterly reworking the meaning of freedom in the United States. Seo’s sweeping account takes us from the beginnings of traffic enforcement, as police departments were transformed from foot patrols to motor cops; through Prohibition, where the automobile played a vital role in the cat-and-mouse game of liquor control and the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches began to be riddled with exceptions; to the modern era, when the phrase “driving while black” emerged to expose a racialized policing of automotive conduct that in fact continued unabated from the Jim Crow Era to the 21st century. This is a book that scholars will admire for its creativity and careful research, while lay readers will never look at getting behind the wheel in the same way again. – D.S.

– – – – –

The Finalist of the 2019 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is Jessica K. Lowe for her Murder in the Shenandoah: Making Law Sovereign in Revolutionary Virginia.

This beautifully written book is history in a grain of sand writ large. Jessica Lowe masterfully transforms a brawl and homicide into a prism on post-Revolutionary Virginia’s legal system already rife with “tense discussion about what it meant to make law ‘king.’” Murder in the Shenandoah is narrative history and legal history at its finest. Brava! – L.K.

For the year 2018

The Winner of the 2018 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History is Black Litigants in the Antebellum South, by Kimberly M. Welch (North Carolina).

Welch’s meticulous research into obscure and tattered court records of the antebellum American South has yielded some surprising results. The title would encompass freedom suits of blacks wrongfully held as slaves and also criminal suits against slaves. Freedom suits are discussed, but her focus is on free persons of color suing whites, for debts, breach of contract, back wages, and the entire range of civil liability.

Welch’s meticulous research into obscure and tattered court records of the antebellum American South has yielded some surprising results. The title would encompass freedom suits of blacks wrongfully held as slaves and also criminal suits against slaves. Freedom suits are discussed, but her focus is on free persons of color suing whites, for debts, breach of contract, back wages, and the entire range of civil liability.

The surprise is that these free blacks suing whites in the antebellum South had no difficulty finding white lawyers to represent them, and that they often won their cases, even when tried by juries. These legal victories over whites, she argues, gave the free black community a small space of agency and self-autonomy. Welch argues that these results demonstrate that the antebellum South valued property rights, even property owned by Negroes, over a total domination of blacks. One could argue further that it demonstrates the value put on legality itself by antebellum whites over a total white supremacy. That is curious because after the War, whites of the South valued their hegemony over blacks more than legality itself (lynching, barriers to black voting, etc.).

Welch appends a harrowing description of the researcher’s difficulties in locating and even reading these obscure records. So it may be narrow-minded to point out that this is only a case study, involving only four counties of Mississippi and Louisiana. But what a stimulus for further work! She points out that many courthouses were burned by invading Union forces, but there must be many other localities where the antebellum court records have survived and could be used to test her findings (Montgomery, Alabama?).

On top of her careful research and stimulating findings, Welch also writes clearly and made her work a pleasure to read. – DJL, Sr.

– – – – –

Two books won Finalist status for the 2018 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History: Child Labor in America: The Epic Legal Struggle to Protect Children, by John A. Fliter (Kansas) and The Sit-Ins: Protest and Legal Change in the Civil Rights Era, by Christopher W. Schmidt (Chicago).

In Child Labor, John A. Fliter comprehensively and vividly chronicles the complex political and constitutional issues involved in what the title so aptly describes as the “epic struggle” against child labor. This carefully researched book offers new insights into many subjects, including the enactment and judicial nullification of the first two federal child labor statutes, the subsequent failure of efforts to add a child labor amendment to the federal Constitution, and the ultimate enactment during the New Deal of a statute that withstood the U.S. Supreme Court’s scrutiny. The book concludes with a survey of recent efforts to roll back these hard-fought reforms. – WGR

In Child Labor, John A. Fliter comprehensively and vividly chronicles the complex political and constitutional issues involved in what the title so aptly describes as the “epic struggle” against child labor. This carefully researched book offers new insights into many subjects, including the enactment and judicial nullification of the first two federal child labor statutes, the subsequent failure of efforts to add a child labor amendment to the federal Constitution, and the ultimate enactment during the New Deal of a statute that withstood the U.S. Supreme Court’s scrutiny. The book concludes with a survey of recent efforts to roll back these hard-fought reforms. – WGR

In The Sit-Ins, Christopher W. Schmidt carefully analyzes the early 1960s lunch counter sit-ins, in Greensboro, North Carolina and then sweeping across the American South, from the perspectives of the protesting students, their lawyers, sympathizers, opponents, and the Congress that was then considering civil rights legislation that culminated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The book describes the legal difficulty of using the 14th Amendment to protect protestors because the private owners of public accommodations are not the “state actors” that the 14th Amendment was designed to reach. As a result, the monumental 1964 Act was placed under the Congress’s commerce clause powers and not the 14th Amendment. Schmidt pays particular attention to the squabbles within the Supreme Court over the scope of the 14th Amendment in the struggle for equal accommodations, and writes clearly about the legal issues involved. – DJL, Sr.

In The Sit-Ins, Christopher W. Schmidt carefully analyzes the early 1960s lunch counter sit-ins, in Greensboro, North Carolina and then sweeping across the American South, from the perspectives of the protesting students, their lawyers, sympathizers, opponents, and the Congress that was then considering civil rights legislation that culminated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The book describes the legal difficulty of using the 14th Amendment to protect protestors because the private owners of public accommodations are not the “state actors” that the 14th Amendment was designed to reach. As a result, the monumental 1964 Act was placed under the Congress’s commerce clause powers and not the 14th Amendment. Schmidt pays particular attention to the squabbles within the Supreme Court over the scope of the 14th Amendment in the struggle for equal accommodations, and writes clearly about the legal issues involved. – DJL, Sr.

– – – – –

The winner of the 2018 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction is Louisa Hall’s Trinity

The winner of the 2018 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction is Louisa Hall’s Trinity

The novel explores Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, through his interactions with seven imagined characters from 1943 to 1966. Speaking in “testimonials,” the characters concentrate more on their own lives despite the major world events unfolding around them. Throughout, Oppenheimer appears familiar yet enigmatic. Excellent historical fiction has the power to reveal emotional truths that history cannot, and Trinity does just that through its ingenious form and compelling prose. – VL.

– – – – –

The Finalist for the 2018 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction is Nick Dybek for his The Verdun Affair (Scribner)

Set in Verdun, France and Bologna, Italy in the aftermath of World War I (with a small portion in 1950s Hollywood, California), the chief protagonists are American. A young man works gathering up bones from the former Verdun battlefield for an ossuary when a young woman arrives in search of information about her husband who was reported missing in action. She was one of many American women who roamed Europe searching for missing husbands in the years following the armistice. The two strike up a romance, and then travel to Bologna where a doctor is treating a mysterious shell-shocked soldier who has lost all memory. Circumstantial evidence suggests he might be the husband. A third major character enters the scene, an Austrian journalist who has his own interest in this mystery man.

Set in Verdun, France and Bologna, Italy in the aftermath of World War I (with a small portion in 1950s Hollywood, California), the chief protagonists are American. A young man works gathering up bones from the former Verdun battlefield for an ossuary when a young woman arrives in search of information about her husband who was reported missing in action. She was one of many American women who roamed Europe searching for missing husbands in the years following the armistice. The two strike up a romance, and then travel to Bologna where a doctor is treating a mysterious shell-shocked soldier who has lost all memory. Circumstantial evidence suggests he might be the husband. A third major character enters the scene, an Austrian journalist who has his own interest in this mystery man.

The book is well-written and a page turner. It has numerous elements of interest: a tender affair, the entry of a competing male, a dreadful description of Verdun following the battle, the mysterious amnesiac and the efforts to restore his memory or otherwise identify him, the chaos in Bologna incident to the early years of the Mussolini movement, and the pervasive effects of a significant mistruth spoken by one of the principal characters. – DJL, Sr.

For the year 2017

The Winner of the 2017 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction Is Laurel Davis Huber for Her The Velveteen Daughter (She Writes Press)

Laurel Davis Huber’s Velveteen Daughter composes the documented but unassembled lives of author and artist, as well as mother and daughter Margery Williams Bianco and Pamela Bianco. While Margery Williams Bianco’s Velveteen Rabbit is still cherished by contemporary generations, her daughter Pamela Bianco was arguably more famous in her lifetime. Pamela was a child prodigy discovered in Italy in 1919. After a successful exhibition in London, Bianco gains a patron in Gloria Vanderbilt Whitney who sets the young artist up with a studio and an apartment in New York.

Laurel Davis Huber’s Velveteen Daughter composes the documented but unassembled lives of author and artist, as well as mother and daughter Margery Williams Bianco and Pamela Bianco. While Margery Williams Bianco’s Velveteen Rabbit is still cherished by contemporary generations, her daughter Pamela Bianco was arguably more famous in her lifetime. Pamela was a child prodigy discovered in Italy in 1919. After a successful exhibition in London, Bianco gains a patron in Gloria Vanderbilt Whitney who sets the young artist up with a studio and an apartment in New York.

The novel takes place in the 1940s through 1970s. In the 1940s, we hear the alternating voices of Margery and Pamela during an acute episode of Pamela’s mental illness. Both often allude to the fateful moment when Pamela’s father the bookseller Francesco Bianco enters her into a contest in Turin which serves as the catapult to her international fame. While she is always anxious of her daughter’s celebrity and commissions, Margery is reticent to discourage her husband’s efforts. In the 1970s, Pamela is elderly and largely forgotten by the art world. She has survived one unhappy marriage and one happy one.

The lives of the Bianco family intersect with many artists and authors, some now remembered and some now forgotten. Eugene O’Neill marries and divorces Pamela’s cousin. Pablo Picasso comes to dinner and exchanges drawings with a four-year old Pamela. The Welsh poet Richard (Diccon) Hughes is Pamela’s unrequited and devastating love. While the novel includes vivid scenes of bohemian life both in Wales and Italy, as well as Greenwich Village and Harlem, The Velveteen Daughter is ultimately a novel about the intimate dynamics of familial and romantic love with its myriad expectations and disappointments.

Huber draws on letters and newspapers, and in the notes appended after the novel, carefully delineates fact from fiction. Yet the sources most central to the novel are those created by Pamela and Margery: Pamela’s paintings and Margery’s Velveteen Rabbit. Pamela’s art emerges in exuberant visions. It is spontaneous and joyful, a natural extension of herself. Yet this method does not always please the market, and her father urges her to paint in particular ways that are fashionable at the time to the detriment of her physical and mental health. Yet the velveteen rabbit of Margery’s story becomes real in his loss. So, too, does the Velveteen Daughter become in hers. The narrative ends with plans for a painting “just as I feel. Just as I wish”. — VL

– – – – –

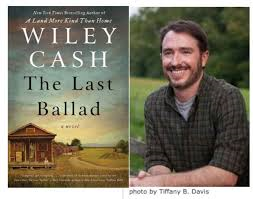

The Finalists for the 2017 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction Are Wiley Cash for His The Last Ballad (Morrow) and Janet Benton for Her Lilli de Jong (Doubleday)

The Last Ballad is a fictionalized biography of Ella May Wiggins, an actual woman, with five children and a husband prone to stray. In the late 1920s she was employed in a carding room of a textile mill located in Bessemer City, North Carolina at the pitiful wage of $9 per seventy-two-hour workweek. Ella and her four children lived in conditions of acute poverty, powerfully shown to us by detailed descriptive writing that is neither angry nor sentimental. Labor unions had just begun to enter the struggle for better conditions in the textile industry. She was attracted to the union movement and began to use her vocal talents by singing at union rallies. Some of Ella May’s songs would later be performed by Woody Guthrie and recorded by Pete Seeger. Eventually, she quit her factory job to work full time for the National Textile Workers Union, a labor organization of the American Communist Party. After a particularly violent labor rally in June 1929, some goons, undoubtedly hired by the owners of the mill, murdered Ella May Wiggins. A precis of this story cannot do justice to the haunting emotions this novel’s lyrical writing evokes in a reader. Highly recommended. – DJL, Sr.

The Last Ballad is a fictionalized biography of Ella May Wiggins, an actual woman, with five children and a husband prone to stray. In the late 1920s she was employed in a carding room of a textile mill located in Bessemer City, North Carolina at the pitiful wage of $9 per seventy-two-hour workweek. Ella and her four children lived in conditions of acute poverty, powerfully shown to us by detailed descriptive writing that is neither angry nor sentimental. Labor unions had just begun to enter the struggle for better conditions in the textile industry. She was attracted to the union movement and began to use her vocal talents by singing at union rallies. Some of Ella May’s songs would later be performed by Woody Guthrie and recorded by Pete Seeger. Eventually, she quit her factory job to work full time for the National Textile Workers Union, a labor organization of the American Communist Party. After a particularly violent labor rally in June 1929, some goons, undoubtedly hired by the owners of the mill, murdered Ella May Wiggins. A precis of this story cannot do justice to the haunting emotions this novel’s lyrical writing evokes in a reader. Highly recommended. – DJL, Sr.

Lilli de Jong tells a sad story that ends well. Lilli becomes pregnant by her well-meaning boyfriend Johan, who intends to marry her. He leaves Philadelphia, where the novel is set, to secure employment in Pittsburgh, unaware that he will soon be a father. Meanwhile Lilli is thrown out of her family home when her pregnancy becomes apparent, and the two lovers are unable to communicate because her father confiscates all incoming mail from the boyfriend, which letters contain his new address. An agent sent by the reimbursement-seeking charity hospital to locate Johan, falsely reports to him that Lilli has married another. Eventually Johan and Lilli reunite under circumstances that try the imagination, but, suspending that, all is well again.

Lilli de Jong tells a sad story that ends well. Lilli becomes pregnant by her well-meaning boyfriend Johan, who intends to marry her. He leaves Philadelphia, where the novel is set, to secure employment in Pittsburgh, unaware that he will soon be a father. Meanwhile Lilli is thrown out of her family home when her pregnancy becomes apparent, and the two lovers are unable to communicate because her father confiscates all incoming mail from the boyfriend, which letters contain his new address. An agent sent by the reimbursement-seeking charity hospital to locate Johan, falsely reports to him that Lilli has married another. Eventually Johan and Lilli reunite under circumstances that try the imagination, but, suspending that, all is well again.

While the couple are separated Lilly has her baby daughter in a charity hospital, refuses the expected gift of the child for adoption. Lilli’s severest trials begin when she is forced to leave the charity. The difficulties facing a single mother in the urban America of 1883 are vividly portrayed. Insult, sexual harassment, theft, lack of employment opportunity all face this determined mother as she is forced to sleep with her daughter in filthy alleys and train stations. It is a stinging indictment of self-righteous bourgeois America that makes 1883 seem worse than but still close to our own day. – DJL, Sr.

– – – – –

I would like to informally discuss four books in lieu of the formal Director’s mentions of previous years. The Twelve-Mile Straight, by Eleanor Henderson (Ecco) is a Southern saga set against the background of Prohibition and the Depression. It is a grim work whose characters experience few transient joys and no enduring happiness. The novel has a remarkable structure, a Roshomon-like style where new interpretations open up as the novel progresses and our understanding of past events become subject to change or major alteration. It reminded me a bit of Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet in that regard, although Twelve-Mile Straight lacks the pleasures and passions of Durrell’s work.

It is not an absolutely novel thing for characters with disabilities to appear in historical fiction. The winner of our own 2014 prize, What is Visible by Kimberly Elkins, had a protagonist, the actual Laura Bridgman, who had been stripped of sight, hearing, taste, and smell by childhood scarlet fever. Even so, disabilities seldom appear in historical fiction, and it is notable that three novels of the past season feature them.

A Piece of the World by Christina Baker Kline (Morrow) is an excellent fictional biography of Christina Olson that describes her relationship with her family and their familial relationship with the famed artist Andrew Wyeth. Christina suffered from a progressive muscular disease that rendered her unable to walk, but was made famous in a sense by Wyeth’s use of her as a model for the famous painting “Christina’s World.” In Manhattan Beach by Jennifer Egan (Scribner), a significant character suffers from major muscle malfunctions, is quadriplegic, and can vocalize only poorly. Although she is only a secondary character, we do read of her impact on her family and on her sister, who is the protagonist. The debility is not named but is undoubtedly cerebral palsy. All She Left Behind by Jane Kirkpatrick (Revell), features a protagonist with a reading disability that she successfully overcame over the course of her life. Not named, it surely is dyslexia.

– – – – –

The Winner of the 2017 David J. Langum Sr. Prize in American Legal History Is The Long Reach of the Sixties: LBJ, Nixon, and the Making of the Contemporary Supreme Court, by Laura Kalman (Oxford)

This exuberant book explains how political controversies during the tumultuous Johnson and Nixon presidencies influenced the nomination and confirmation of U.S. Supreme Court justices and permanently transformed Supreme Court appointments process by intertwining it with the political agendas of presidents, Congress, and special interest groups.

Professor Kalman’s meticulous research introduces newly mined information, fresh insights, and a dazzling array of delicious anecdotes into the controversies that swirled around the Supreme Court appointments of Johnson and Nixon, a subject that already has received substantial attention from historians. She deftly weaves political ideology, party politics, personalities, race, gender, and judicial issues into an exciting account of the forces that influenced the “liberal” appointments of Johnson during the waning years of the Warren Court and the “conservative” appointments of Nixon that attempted, but largely failed, to unravel the decisions of the Warren Court.

Professor Kalman’s meticulous research introduces newly mined information, fresh insights, and a dazzling array of delicious anecdotes into the controversies that swirled around the Supreme Court appointments of Johnson and Nixon, a subject that already has received substantial attention from historians. She deftly weaves political ideology, party politics, personalities, race, gender, and judicial issues into an exciting account of the forces that influenced the “liberal” appointments of Johnson during the waning years of the Warren Court and the “conservative” appointments of Nixon that attempted, but largely failed, to unravel the decisions of the Warren Court.

Although political considerations always have influenced Supreme Court appointments, Professor Kalman explains that presidents beginning with Johnson have been particularly assiduous in attempting to perpetuate their political legacies by nominating men and women whose political views will shape public policy through judicial decisions for decades to come. The rising political stakes of appointments has generated much greater scrutiny of nominees, increased the proportion of controversial nominations, and exacerbated partisanship in the appointments process. – WGR

For the year 2016

The Winner of the 2016 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction Is Michele Moore for Her The Cigar Factory (Univ. of South Carolina Press).

This marvelous debut traces the lives of two working class families in Charleston during the years 1917-1946. The families are similar in many ways: devout and practicing Roman Catholics, headed by matriarchs who work in the local cigar factory, both struggling mightily for survival in severely limited circumstances. Yet they are dissimilar in ways crucial for Charleston in these years: one family is black and the other white, they attend separate churches, the matriarchs work in the cigar factory in segregated tasks and floors, use different restrooms, and receive different wages. Union organization and a strike begin a growing awareness by these two women of each other’s existence and the similarities of their and their families’ lives.

The author describes the difficult lives of these two families, both joys and sorrows, with great sensitivity and beauty. Dialect in novels is tricky, but Moore employs the Gullah dialect selectively and in brief snippets, and in so doing does not detract from the ease of reading the novel but rather adds to its verisimilitude. – DJL, Sr.

The Finalist for the 2016 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Historical Fiction Is Chad Dundas for His Champion of the World (Putnam).

This debut novel portrays the world of American wrestling in the 1920s, when wrestling was more science than show. In lively and economic prose, Chad Dundas narrates the briefly lived comeback of former wrestling champion-turned carnival performer Pepper Van Dean and his card-shark wife who negotiate bootleggers, ruthless carnival owners, and the rise of professional wrestling. At the centre of the novel is a fictional match between the reigning champion and an underdog contender. Dundas’s training as a sports journalist shines through in the suspense of his scenes, in and out of the ring. Furthermore, the characters and the historical setting are vividly realized. – VL

The Winner of the 2016 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History/Biography Is Risa Goluboff for Vagrant Nation: Police Power, Constitutional Change, and the Making of the 1960s (Oxford University Press).

The extremely vague vagrancy laws allowed police to arrest somebody for such things as aimless wandering, seeming out of place in a setting, or being without money or employment to provide their support. Police loved these laws since it gave them almost unlimited discretion to lock persons up for such short sentences, 15-30 days usually, that they were almost never appealed. This, the police thought, prevented crimes that these unseemly persons might otherwise have committed. In fact, this wide discretion fostered grave abuse of law enforcement’s powers.

Before 1850 the vagrancy laws had been used sporadically, usually against undesirables, “tramps,” and those who refused to work during periods of labor shortage. During the 1950s and 1960s, the primary period reviewed by this book, the use of vagrancy laws was expanded and used to arrest homosexuals, civil rights activists, interracial couples, beatniks, hippies, and opponents to the Vietnam War.

Judicial pondering about the constitutionality of these laws in the 1960s ultimately led to the Papachristou v. Jacksonville decision in 1972. In that case the United States Supreme Court held that vagrancy laws as traditionally understood were unconstitutional for their vagueness and lack of any specific conduct declared wrongful. This excellent book is well-written and clearly accessible to the general educated reader. In addition the author has provided an abundance of historical and cultural context for the 1960s, so the reader is able to understand the operation of the vagrancy laws and their destruction as an integral part of the times. – DJL, Sr.

Two books won Finalist status for the 2016 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal history: Ballot Battles: The History of Disputed Elections in the United States, by Edward B. Foley (Oxford University Press) and The Great Yazoo Lands Sale: The Case of Fletcher v. Peck, by Charles F. Hobson (University Press of Kansas).

In Ballot Battles, Foley analyzes the details of American elections, state and federal, in which the vote was contested, beginning with the 1781 dispute over the votes cast in an election for a seat on the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania and ending with a 2008 disputed senatorial contest in Minnesota. Appropriately, he spends more time on the major contests, Hayes v. Tilden in 1876 and Bush v. Gore in 2000, but not to the neglect of lesser disputes.

The book focuses on irregularities with vote casting or counting, and therefore only briefly discusses the few election disputes that arose out of the structure of the electoral process, as in the elections of 1800 (tied electoral college vote caused by original structure of Electoral College before 12th amendment) and 1824 (no candidate received a majority of the electors, and election went to the House of Representatives). However, there are an abundance of very close elections that generated disputes over the validity of votes cast or their counting.

Foley attributes the disputes surrounding extremely close elections to a flaw in the original design of our constitutional order: the failure of the founders to provide guidance over the disposition of these disputes. He includes a brief discussion of proposed reforms. – DJL, Sr.

In The Great Yazoo Lands Sale, Professor Hobson vividly portrays the fascinating cauldron of legal, social, economic, political, and ethnic forces and colorful personalities that generated the Supreme Court’s decision in Fletcher v. Peck, which nullified the Georgia legislature’s repudiation of scandal-ridden sales of Indian lands to speculators. Hobson demonstrates the importance of the case in protecting vested property interests and establishing the Court’s hugely important role in reviewing the constitutionality of state legislation. – WGR

For the year 2015

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Historical Fiction, Winner for 2015:

Good Night, Mr. Wodehouse by Faith Sullivan (Milkweed)

Good Night, Mr. Wodehouse is an exquisite gem. Nell Stillman, the protagonist, is an Everywoman. She lived almost her entire adult life in an apartment above a meat market in the small town of Harvester, Minnesota. Widowed at age 24 with an infant, Nell became the third grade teacher of the town’s school for 37 years. Almost nothing in the large scale of life occurred to Nell, yet many chaotic events in everyday life challenged her. Nell’s son returned shell-shocked from World War I; a young woman she nurtured became pregnant and left the small town in disgrace; some in the town blamed Nell for her charge’s disgrace; and Nell herself found love late in life with a fine man who died just before their scheduled marriage.

Aside from her own grit and independence, Nell had three other means of coping with life. The first was her small number of excellent friends. The second was the love she shared with a man over many years, yet blasted away by her lover’s untimely death. The third, and most important, was her love of reading. She read many novelists but fell in love with the novels of the British writer P.G. Wodehouse. She found time every evening to read, and, in a major theme of this book, Nell had the strength to carry on through the transformative power of reading.

The time of Nell’s adult life, c. 1900-1961, saw many historical changes of significant character, for example, numerous improvements in appliances and other implements of women’s work, W.W.I, women’s suffrage, electrification, prohibition, W.W.II, and so on. The book does not neglect these historical events but presents then from the satisfying perspective of what they meant to this little town, and what they meant to Nell Stillman. Highly recommend. – DJL, Sr.

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Historical Fiction, Honorary Mention for 2015:

The Race for Paris by Meg Waite Clayton (Harper)

Inspired by true events and historical figures, the author tells the overlooked story of World War II female war correspondents and their quests to be the first to report the Allied liberation of Paris. This powerful story sweeps the reader into the front lines of battle where conditions for the correspondents are nearly as stark and dangerous as they are for the troops. Well researched and rich with vivid descriptions of wartime France, Clayton skillfully keeps the focus on the characters’ ambitions and personal dilemmas. Yet, the messiness and horror of war never leave the page. Layered with complicated relationships and motives, this gripping story about the correspondents’ quest to record events while dealing with their own quandaries fully engages the reader.

What especially sets The Race for Paris apart is its fresh examination of female correspondents in the front lines. Many novelists have written about World War II, but Meg Waite Clayton brings a new perspective not only to the war but to the risks endured by journalists and photographers. – AW

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Legal History/Biography, Winner for 2015:

Who Freed the Slaves? The Fight over the Thirteenth Amendment, by Leonard L. Richards (University of Chicago Press), wins the David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History for 2015. Richards vividly describes the messy process of the Congressional adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment before its submission to the states for ratification. Many today think that this amendment was simply an inevitable culmination of the Emancipation Proclamation, but that thought is incorrect. Even in the final stage of the Civil War, many opposed an outright ban on slavery. Richards explains this opposition and brings forward forgotten figures, such as Congressman James Ashley of Ohio, who were far more influential in securing the passage of the Amendment than Lincoln, who actually dragged his feet until the last moment before passage. Clearly and engagingly written, Richards has also based his work on sound scholarship exhibited in extensive endnotes. – DJL, Sr.

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Legal History/Biography, Honorary Mention for 2015:

The 2015 Honorable Mention for American Legal History/Biography goes to Nancy Woloch’s A Class by Herself: Protective Laws for Women Workers, 1890s-1990s (Princeton University Press, 2015). Professor Woloch meticulously examines the complex political, constitutional, and social forces that contributed to the rise and fall of Progressive Era gender-specific legislation to protect the health and safety of women through minimum wages, maximum hours, and regulation of workplace conditions. The book traces the intense controversy over such laws among advocates of women’s rights, who increasingly believed that they hindered rather than promoted the interests of women by reinforcing gender distinctions and impeding equal rights. The book also explains how protective laws for women helped pave the way for similar measures for all workers during the Progressive Era and the New Deal. – WGR

For the year 2014

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Historical Fiction, Winner for 2014:

What is Visible by Kimberly Elkins (Twelve)

This novel lyrically revives a significant and intriguing figure in the history of disability. Laura Bridgman (d. 1889) was a celebrity in her lifetime. Stripped of sight, hearing, taste and smell by scarlet fever in her childhood, Bridgman served as a poster child for the Perkins School for the Blind and various intellectual causes such as phrenology and anti-Calvinism.

Laura’s desperate need to command attention and to please others conflicts with her desire for a private life distinct from any larger cause. Through meticulous archival and imaginative labor, Elkins provides Bridgman with an inner life that offers a daring and convincing account of a woman who observes and communicates only through touch. As the author articulates in the appendix, the novel concerns “what might have happened as well” rather than “what might have happened instead.” Following this method, Elkins attends to Bridgman’s parameters for pleasure, longing, deprivation and defiance with a narrative voice that evokes sympathy without sentimentality.

Most of the novel gathers snugly around Bridgman’s life and perceptions, interspersed with the perspectives of those around her. In addition to the host of passing contemporary notorieties, such as Charles Dickens, who visit and comment upon her, Bridgman’s life intersects with prominent figures in more sustained ways. These include her doctor Samuel Gridley Howe, the poet Julia Ward Howe, and even the abolitionist John Brown.

What sets this novel apart is the author’s ability to imagine Laura Bridgman’s world and to give her a powerful narrative voice. With skill and compassion, Elkins portrays Bridgman as a complicated character whose strengths and flaws grow more complex as the story progresses. Historical details enrich the story, and the author deftly exposes the care and treatment of the disabled during the 1800s. This is American historical fiction at its best. – VL

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Historical Fiction, Honorable Mention for 2014:

Rush of Shadows by Catherine Bell (Washington Writers’ Publishing House)

Small farmers in the coastal hills of Northern California’s Sacramento Valley and the indigenous Digger Indians they encountered in the 1850s are the moving forces in this sparsely but beautifully written novel. While there are fine passages describing the beauties of the land and the methods adopted by these pioneers for shelter, food, and formation of communities, the major theme is the relationship of these farmers with the local Indians.

The Indians of Northern California were wholly unlike their heartier cousins of the plains or the deserts. Americans referred to them as “diggers” because the beneficent California climate permitted them to thrive by gathering up roots and seeds coupled with minimal hunting. Their primitive technology rendered them absolutely defenseless against the invading hoard of Americans who, wanting their lands for conventional farming, raped and murdered the Diggers, stole their lands, and herded the survivors onto miserable reservations.

The book’s chapters are told from the perspectives of different characters, although dominated by Mellie, wife of an American settler, and Bahé, granddaughter of the Indian band’s shaman. Tension mounts throughout the book, and the ultimate outcome comes dramatically but without sentiment. The characters are drawn well, two of them beginning with strong anti-Indian feelings that soften over time. In the hands of a lesser writer, Mellie could have become a stock character of a strong woman who saves the tribe from removal. Here, more sensitively and more realistically, her influence is smaller and more personal: providing medicine for one Indian child, a job for one woman, and a warning about an impending capture. Bahé is even more delicately drawn as a strong woman who realizes the futility of fighting the white man, but who draws on her inner strength as the new spiritual leader of her band to accommodate and preserve as much of the old ways as is possible.

This is truly fresh material. The Trail of Tears is well-known, but Indian removals in California are relatively obscure. The characters are well-drawn and the descriptions vivid. A beautiful book. – DJL, Sr.

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Historical Fiction, Director’s Mention for 2014:

The Moor’s Account by Laila Lalami (Pantheon Books)

While The Moor’s Account does not fully meet the requirements for the prize, the Director commends this excellent novel.

“It was the year 934 of the Hegira, the thirtieth year of my life, the fifth year of my bondage – and I was at the edge of the known world.” So begins this extraordinary, pitch-perfect work of historical fiction about the Narváez expedition in Florida. The narrator is Mustafa al-Zamori, a slave from Azemmur whom the Castilian explorers call Estebanico. Mustafa, one of four expedition survivors and who is haunted by his own demons, tells an unvarnished account of the exploration of Florida and the Southwest. The 600-man expedition (1528-1536) is a disaster from the moment the ships arrive on the Gulf Coast. The leaders engage in power struggles, the expedition gets lost, and within a few years all but four men are dead from accidents, starvation, and disease. These survivors cross all the way along the southern border of the present United States, from Florida to Mexico. The expedition’s encounters with native peoples are equally harrowing. Mustafa’s account painfully foreshadows the future of Native Americans.

The novel is rich with moral quandaries about what people will do to survive. The author’s attention to historical and ethnological detail is remarkable as is the scope of the story which covers Africa, Spain, and the New World, including Mexico. Yet the details never slow the pace or the excitement of the story.

What especially sets The Moor’s Account apart is the author’s ability to bring alive an extraordinary piece of history told by an overlooked narrator. – AW

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Legal History/Biography, Winner for 2014:

The winner of the David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History/Biography for 2014 is Baseball on Trial: The Origin of Baseball’s Antitrust Exemption, by Nathaniel Grow (University of Illinois Press). This book describes in rich detail the rivalry and litigation between the three American baseball leagues in the early twentieth century: the upstart Federal League and the better-established American League and National League. Through a complex set of personalities, deals, and litigation, all of which Grow well chronicles, the issue of whether the leagues were subject to the federal anti-trust laws was ultimately presented to the United States Supreme Court in the landmark case of Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, decided in 1922. It certainly seemed as though the leagues were anti-competitive. They controlled many phases of baseball including hiring, salaries, movement of players from one team to another, even the sale of teams. Yet Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes writing for the Court concluded that baseball was not even interstate commerce, notwithstanding the regular crossing across state lines for teams to play one another. This story constitutes the major portion of Grow’s work.

A rushed epilogue traces the later judicial treatment of this exemption, and the impact of collective bargaining, but lacks discussion of Congress’s belated entry into the arena through its curiously limited Curt Flood Act of 1998.

Of particular interest is the skill with which Grow delineates the trial strategies of counsel, discussing several weaknesses in the way the plaintiff’s case was presented. He is kind to Justice Holmes in reminding the reader that the huge apparatus of interstate television, radio, and advertising for baseball simply did not exist in 1922, and it was possible with a straight face to claim that professional baseball was not engaged in interstate commerce. – DJL, Sr.

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Legal History/Biography, Honorary Mention for 2014:

The 2014 honorable mention for American Legal History/Biography goes to Her Honor: Rosalie Wahl and the Minnesota Women’s Movement, by Lori Sturdevant (Minnesota Historical Society Press). This engaging biography of Rosalie Wahl (1924-2013), who in 1977 became the first woman to serve as a justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court, provides a comprehensive account of the life and accomplishments of an important jurist. It also offers significant insights into the struggles of women to erode gender barriers in the legal profession and in politics in Minnesota and throughout the nation during a period of rapid social change. – WGR

For the year 2013

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Historical Fiction for 2013:

Crossing Purgatory, by Gary Schanbacher (Pegasus). The title carries a double meaning, referring to the crossing of a river in western Kansas where the protagonist settled and made his home, and also the crossing of his own, personal purgatory. A spiritual dimension enlightens this book, not pushed upon the reader and so subtle that a uninterested reader could ignore it but then miss much of the book’s value. When we first meet Thompson Grey he is matching westward from his family farm in Indiana, filled with guilt and remorse. He joins a wagon train traveling westward on the Santa Fe Trail, then settles in a ranch operated by the captain of the wagon train in western Kansas. Throughout the trip and in his stay at the ranch Grey acts humanely, responsibly, and is esteemed by all. Yet his guilt remains with him as gradually the reader understands its basis. His root sins, he understands, are cupidity and the coveting of land, and these he believes had caused the death of his wife and children back in Indiana. In the west he is eventually tempted again, but he finds the means to resist, and while his method might seem extreme to many, it is true to the man and his history.

Irrespective of the protagonist’s inner struggles, the story itself is well-told and exciting. Once again, we have an excellent novel that paints the west with more depth than is usual, that portrays the evil and the hardship as well as the rewards. – DJL Sr.

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Historical Fiction, Honorable Mentions for 2013

Seven Locks, by Christine Wade (Atria). Set in the rural Hudson River Valley at the time of the American Revolution, the narrator has far more than her share of difficulties. Her husband, lazy and often absent, finally disappears. Her daughter and son are adolescents and difficult to deal with. Then come the pillages and desolation caused by both sides of the Revolution. She flees and leaves the country. Years later her husband, with a fantastic excuse for his disappearance, returns to the settlement, where the daughter and her husband now live. There is much here about the interior life of the characters, but what makes this book most singular is that it is set among farmers of Dutch descendent. It provides insight into the Dutch colonists and their successors, a group here well-described and about whom little has been written. – DJL Sr.

Swimming in the Moon, by Pamela Schoenewaldt. (Morrow). Lucia and her mother Teresa emigrate from Italy and arrive in Cleveland in 1904. They have the usual immigrant struggles, working long hours for poor pay. Additionally, the mother’s mental health becomes steadily worse, and Lucia faces a conflict between her own ambitions and her duty to her mother. The news of New York’s Triangle Factory fire galvanizes Lucia into participation in the local labor movement. The author has richly drawn her characters and clearly portrayed the emotional tolls cast on the new immigrants. What really sets this novel apart, however, is its depth of social history, the detailed accounts of immigrant life. – DJL Sr.

Langum Prize for American Legal History/Biography for 2013

The winner for 2013 is Obscenity Rules: Roth v. United States and the Long Struggle over Sexual Expression, by Whitney Strub (University Press of Kansas). This long title is perfectly appropriate since the book covers far more than its principal case, although it does discuss Roth well and in detail. However, the book also analyzes American attitudes and law regarding obscenity from our colonial times to the present. In doing so its scope extends well beyond the time of Roth in 1957 to porno chic and the disparate feminist interpretations of pornography of the 1960s and 1970s and beyond to the present. A great virtue of Strub’s work is that he brings in a great variety of background factors, including changing social mores and even changes in technology, to inform our understanding of changes in legal norms regarding obscenity, a legal term, and pornography, a cultural construct. – DJL, Sr.

Honorary Mention Langum Prize for American Legal History/Biography for 2013

The 2013 honorable mention for American legal history goes to Father, Son, and Constitution: How Justice Tom Clark and Attorney General Ramsey Clark Shaped American Democracy (University Press of Kansas). The author, Alexander Wohl, has thoroughly and engagingly explained how Tom C. Clark and his son Ramsey Clark made enduring contributions to American constitutional law, especially in cases involving civil rights, free speech, personal privacy, and presidential power. Both were united in their dedication to the freedom of citizens from intrusive government, despite differences that reflected their personalities, interests, and the times in which they worked. Wohl shows how the elder Clark accomplished many of his goals through established institutions while his more iconoclastic son often initiated bold actions to challenge injustices. Wohl’s highly contextual work offers fascinating insights into the Supreme Court during Tom Clark’s tenure from 1949-1967 and the Johnson Administration during Ramsey Clark’s service as U.S. attorney general from 1967-1969. – WGR

For the year 2012

David J. Langum, Sr. Prize for American Historical Fiction for 2012:

The Cove, by Ron Rash (New York: Ecco, 2012). This powerful and atmospheric novel takes place in the North Carolina mountains during the final year of World War I. The story revolves around a sister and brother, Laurel and Hank, whose family home in an isolated cove is darkened by cliffs, ridges, and local superstitions. Both are wounded people. Hank lost part of an arm while serving in the army in France. Laurel has a birthmark on her shoulder and neck, and is feared and ostracized by the community. Their lives change when they take in a stranger who plays the flute but does not speak.

The Cove is American historical fiction at its best. The writing is lyrical and the novel is rich with symbolism, yet the prose does not overshadow the story. Rash’s use of regional language adds depth to the characters and never strays toward ridicule. Small details – a flour-cloth dress, a hearing machine with wires and a dial, wagon and automobile tracks on the same road – speak to time and place. With a light touch, Rash balances anti-German sentiment and America’s increasing impatience with the war. The sense of doom established in the prologue heightens with each ensuing scene until the novel ends with a satisfying conclusion.

There is much to commend about The Cove. For the purposes of this prize, its remarkable achievement is the insight into a little known historical event: the seizure of the German ocean liner, the Vaterland, and the placement of its crew in a North Carolina internment camp. A.W.

David J. Langum, Sr. Historical Fiction Honorable Mention for 2012:

Slant of Light: A Novel of Utopian Dreams and Civil War, by Steve Wiegenstein (Saint Louis: Blank Slate Press, 2012). This well-written debut novel describes the travails of a utopian colony in southern Missouri during the late 1850s. At a deeper level it is also a meditation on the decline of order – social order, sexual order, and political order – all clearly delineated but with no causal explanation other than “homo homini lupus.” Man is a wolf to man, and probably an ample reason.

James Turner is an itinerant lecturer, expounding on the merits of a proposed utopian community to be founded on the principles of democracy, balance, trust, openness, and harmony. A farmer in southern Missouri offers him land, and Turner and his small band of followers begin their agricultural settlement. Turner’s wife Charlotte at first is a somewhat quiet character, but over time and tribulations becomes more forceful. Soon a philosophical Adam Cabot, an abolitionist, joins their settlement. Much of the novel traces the community’s efforts, failures, and successes.

Social order, at least as defined by the founding principles, breaks down very quickly. Largely because of the recalcitrance of a small number of the colonists, Turner increasingly imposes his will in community meetings, employing deception, secrecy, and sometimes force. Sexual order is threatened by Charlotte’s valiant struggle to keep her deep attachment to Adam on a platonic basis. James succumbs fairly easily to the allurements of a young colonist, Marie, and is caught by his wife.

The collapse of political order arrives with the coming of the Civil War. Missouri is a border state with bitter feelings on both sides of secession and slavery, and also the need to fight for either. The membership of the colony itself is divided. Turner struggles to maintain the group’s neutrality, but ultimately more and more members leave the join the fighting, and the settlement is left in virtual suspension, with only Charlotte to hold on. Wiegenstein handles the coming of the Civil War adroitly, refusing to foreshadow events. The reader hears of incidents leading to the war only as the community becomes aware of them.

Congratulations are due to Wiegenstein for this lovely book on a neglected border state and also are due to the new small press that published it. D.J.L., Sr.

2012 Langum Prize in American Legal History/Biography:

The winner of the 2012 David J. Langum, Sr. Prize in American Legal History or Biography is Samuel Walker for his Presidents and Civil Liberties from Wilson to Obama: A Story of Poor Custodians (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). This work is a tour de force that that discusses virtually every significant event, judicial decision, or government activity affecting civil liberties in America from 1913 (Wilson’s inauguration) to 2009 (Obama’s inauguration). Organized primarily by Presidential actions or reactions, the author analyzes each President by his civil rights record, and, finding them all to be lacking, concludes with the subtitle of the book, that on the whole they have been poor custodians of Americans’ civil liberties.

This is no dry discussion of changing legal doctrine. As appropriate, Walker is careful to bring to the discussion how changes in the economy, public opinion, social conditions, wartime fears, and protests have been inextricably involved with the expansion and contraction of civil rights. He brings a generally liberal and civil-libertarian outlook to his work, and is candid to disclose that he has had thirty years of involvement with the ACLU. Nonetheless, he is scrupulously fair. Where Presidents generally thought of as conservative did something favorable to civil liberties he describes it and renders praise. An example of this is President Harding’s pardon of Eugene Debs, a notable victim of Wilson’s World War I suppression of free speech. Likewise where Presidents generally thought of as liberal did something unfavorable to civil liberties, he describes that too and criticizes. An example of this is President Truman’s Loyalty Program and its use of guilt by association. He makes a clear case that disrespect for civil rights is nonpartisan.

General readers should not be discouraged by the footnotes being placed where they should be positioned for convenience of reference: at the foot of each page. Although many facts and much history are packed within this 510 page volume, Walker has written an extremely readable account. DJL, Sr.

2012 Honorary Mention Langum Prize in Legal History/Biography:

Honorable mention goes to R. Kent Newmyer for his The Treason Trial of Aaron Burr: Law, Politics, and the Character Wars of the New Nation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). This short well-written volume focuses, as implied by the title, on the trial of Aaron Burr for treason and high misdemeanor. Newmyer only briefly discusses background: the confusing facts of the alleged conspiracy to break off western portions of the nation, the motivations for Jefferson’s denunciation of Burr, or the puzzling aspects of the prosecution (especially why Burr was not charged with a much more easily proven violation of the Neutrality Act in addition to the difficult Treason and High Misdemeanor charges). Instead, Newmyer concentrates on the pretrial activities and trial itself. Although the trial did much to elucidate the American law of treason, it cannot be said to have resolved the factual issues that lay behind the conflict. What Burr was really up to may always remain shrouded in mystery, and in our confusion we can take some comfort with the fact that it was equally confusing to the contemporaries of the events. DJL, Sr.

For the year 2011

Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction for 2011:

Julie Otsuka, The Buddha in the Attic (New York: Knopf, 2011). This short, poetic book describes the experience of the Japanese “picture brides” who were brought over in the very early part of the 20th century to marry Japanese men working in the United States, mostly as farm laborers. The writing is beautiful, and, although the book is sparse, each word carries weight. The Buddha describes their passage over, their meetings with their new husbands, and their difficult relationships with Anglos. It follows them working on the farms and through the Depression, and takes them up to their rounding up for imprisonment in the American concentration camps of W.W. II. The Buddha has an unusual style. It describes a particular person or situation in two or three tight third person sentences, and just as often does the same in the first person plural (“we” or “one of us”). The reader at first feels disoriented, but quickly this babble of individual situations and persons blends together into a harmonious chorus.